Emma Goodall and I just had a book published to support parents to help build resilience in their autistic kids. One of the key concepts we articulated in the book as an essential part of building resilience is that of a ‘Place of safety’

Building resilience needs to start from a solid base. A child needs to have a place they can go to – physically or through their imagination and memory – where they feel safe, supported and have some sense of control and agency. Parents can help create this kind of environment for their child and ideally, beyond that friends and relatives and the child’s school. Self-confidence and, through it resilience, often begins when the child has their own ‘place of safety’. Most people are more confident when surrounded by people who believe in them and when they have a positive sense of self and a belief in themselves as capable people. These things are a ‘place of safety’. E Goodall and J Purkis Parents’ Practical Guide to their children aged 2-10 on the autism spectrum

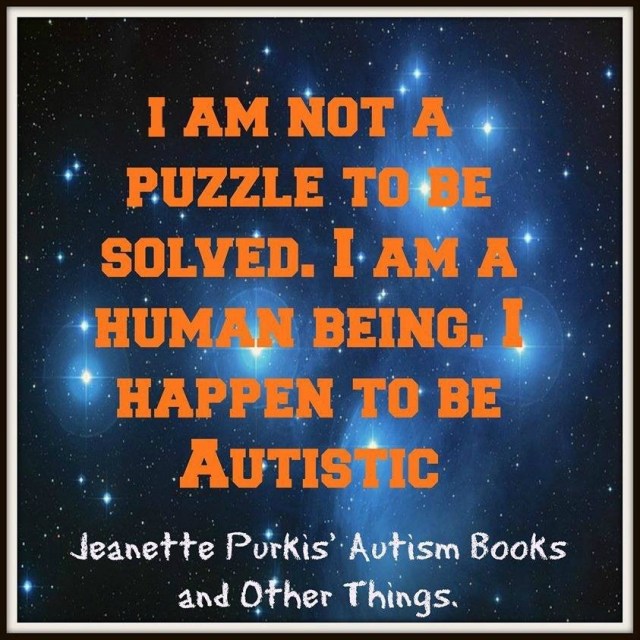

This is not just for autistic kids – everyone needs this space of being validated and respected as they start their life’s journey.

One of the great things about a place of safety is that it enables the young person to build their self-esteem and self-worth. It helps them to understand that they are someone who is loved and cared for. This can give them support and protection as they travel through life.

A place of safety is sometimes with people other than family members as some families are toxic. this can more more difficult to establish given society;s expectations that family is always supportive na deposition place. I have et so many people who desperately wanted their family to be a place of safety but it wasn’t.

I want to talk about my own place of safety.

I was born in the 1970s – a very different world to now. There was no Asperger’s diagnosis, the focus was on disciplining ‘naughty’ children and the word ‘parent’ was only ever used as a noun and never a verb.

I have a family who I think it is reasonable to say are fairly quirky and neurodivergent. Home was a supportive and happy place but there was clearly a mismatch between parenting wisdom at the time and what was needed to support my development. From what I am told there was always someone quick to judge my parents – and especially my mum – for ‘doing it wrong.’ However my perception was that family life was positive and supportive and validating – definitely a place of safety.

For me, the place of safety was tested and challenged relentlessly, mostly by school bullies. One of the beautiful aspects of a place of safety is that it validated\s the young person. Validation means that you are treated in a way to suggest you have value as a human being and have the right to be yourself. There is an opposite to this – invalidation. Invalidation is where a person is treated as if they don’t matter. They are treated like they are unimportant. Invalidation can take many forms – violence and abuse and for autistic kids and young people it often is delivered via the school bully or bullies. Bullying is clearly a form of invalidation.

In my childhood and teen years, all the good work of my family and the place of safety it had given was stripped away by years of bullying and violence. My confidence and self-worth had all but disappeared by the end of year 12. I was so invalidated that I wanted and actively sought out negative experiences – the company of dangerous people and criminals and all that entailed.

This resulted in a place where there waa s no safety at all – psychological or physical. I was the most vulnerable of people. I continuously sabotaged my life and deliberately made really poor choices. The pace of safety seemed to be a lost thing. but something was going on which I was unaware of but which helped me to change my life. My family simply never left, never disowned m or distanced themselves from me. Whatever terrible things I did they would still be there, filed wiht love. I was the most wretched human being who everyone expected to die – a prisoner, a drug addict, untreated mental illness persuading me to do destructive things. But every month my parents were there to visit, buying me a packet of cigarettes despite them being health conscious, putting money into my account which meant I had a radio in my cell to keep my sane as weeks turned into months and years. My grandma in England wrote me a letter each week and always responded. I have a box of her letters in my bedroom waiting for me to be in the right place to read them.

Through their staying in touch and engagement my family were reintroducing the place of safety into my life. I didn’t really notice it at the time but what it did was keep me connected with a positive and kind world. In 2000 when I changed my attitude and with it changed my life I was not alone. So many people I knew at that time lost their connection to family and friends but I didn’t for which I am very grateful.

Over the 18 or so years since me deciding to change my life, the place of safety has not been forgotten. If anything it has grown. My place of safety is a vibrant and changing thing and it is a great thing to cultivate. My place of safety includes family members and friends and even outputs like my TEDx talk. The place of safety is a great thing to give children to help them on their path through life. It does help with the acquisition resilience and self worth. And it is something which a person can carry with them through their life. You can make conscious choices about who and what you want in your pace of safety. It can provide a great buffer against invalidation.

The place of safety can be applied at different times in life. As the story I told demonstrates, the place of safety can be reintroduced later in life. I can be continuous or it can be something in childhood which doesn’t carry on into later life. I know for me it is a really useful way of thinking about how I overcame adversity and built the life I have now, which is rewarding and meaningful – most of the time at least!

Little me – living with my supportive family was a big positive

Little me – living with my supportive family was a big positive